When Donald Trump was first elected president in the fall of 2016, his elevation to the most powerful office in the world seemed like an aberration. He had faced a particularly unpopular Democratic opponent. He had lost the popular vote. There were all kinds of rumors about assistance from foreign powers. And then there was the nature of Trump’s electoral coalition: Heavily reliant on older white voters, it was widely interpreted as the last stand of a demographic bloc that was destined to decline in importance over the following years.

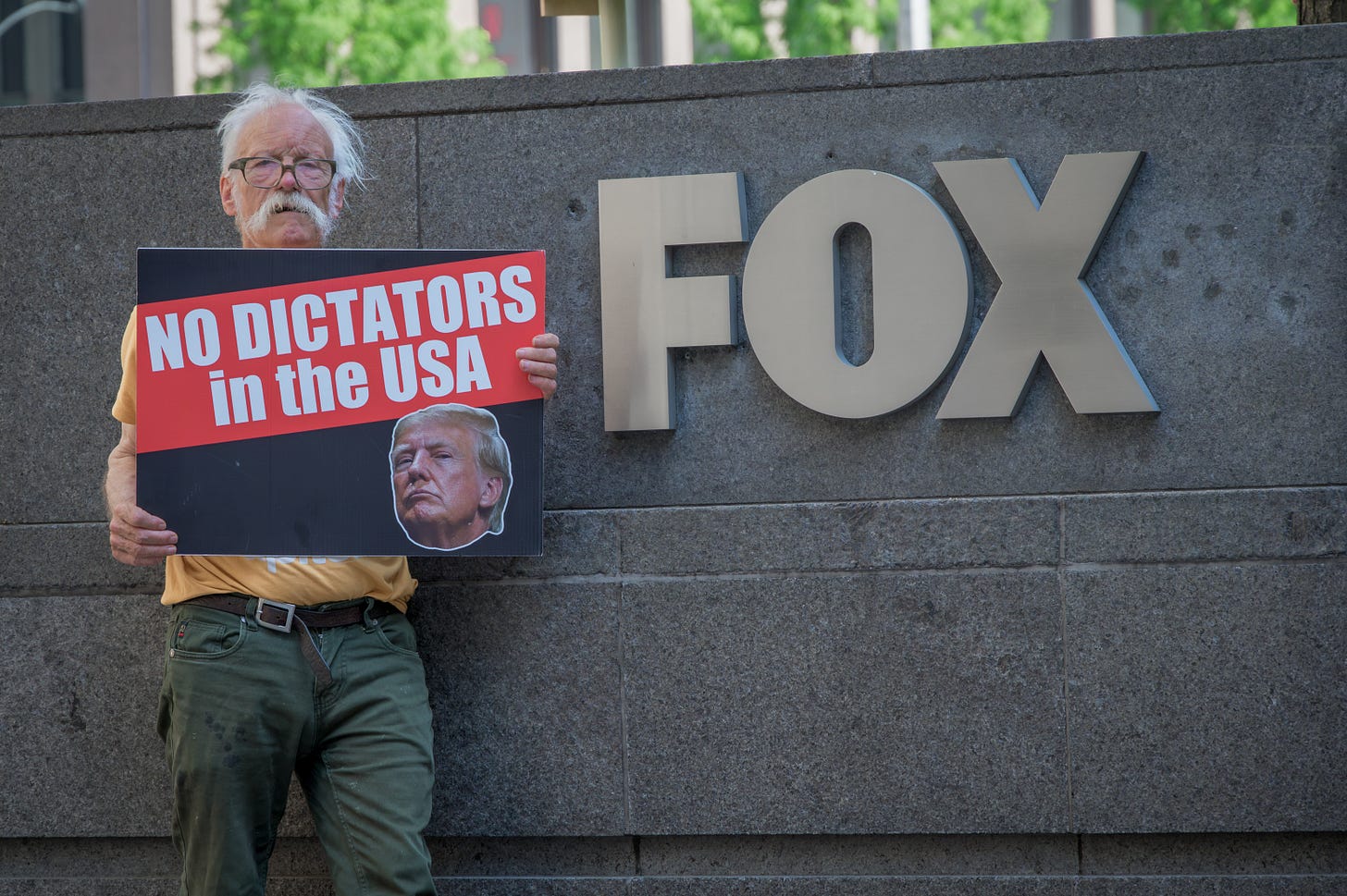

All of these factors fed into a particular set of prescriptions about how best to oppose Trump’s presidency: total resistance. If Trump had been elevated to the White House through a series of unfortunate coincidences, then the best way to neutralize the danger he posed to American democracy seemingly was to oppose him in every possible way. The goal of the #Resistance was to stop Trump from taking over our institutions or becoming sufficiently “normalized” to gain a permanent foothold in American politics. If only his opponents could withstand this unique period of acute danger, it was assumed, things would go back to normal.

Make sure that you don’t miss any episodes of my podcast! Sign up for ad-free access to all of its episodes by becoming a paying subscriber and adding the private feed to The Good Fight now.

The paradigm of total resistance inspired a wide range of tactics. Some were self-defeating or outright delusional. During the transition, serious academics called on the Electoral College to elevate Hillary Clinton to the presidency even though she had lost the election. Cable news hosts on MSNBC spent months and years arguing or insinuating that Trump was an actual Russian agent. Some protest movements tried to win over hearts and minds; plenty of others self-consciously refused to appeal to anybody who might have voted for the president. This was the predominant feeling among many progressives: The people who had voted for Trump, many of my friends and acquaintances told me, were irredeemable racists and bigots. Trying to change their minds was futile, perhaps even morally suspect. The only question should be how to outmobilize them.

Other tactics inspired by the strategy of total resistance were—or at least promised to be—more subtle and effective. For example, there was still a widespread assumption that most Americans held in high regard certain categories of professionals who claimed to be nonpartisan. Many opponents of Trump therefore believed (as did I, at the time) that getting hundreds of former judges or military officers to denounce Trump might make a real impact on public opinion. Enormous effort was invested in organizing a variety of public letters in which such people, citing their professional experience and nonpartisan standing, warned about various aspects of the Trump administration.

And then of course there were the endless attempts to investigate or impeach Donald Trump. There was James Comey’s investigation into his ties to Russia and the long-running probe by Special Counsel Robert Mueller. There were congressional investigations into everything from his tax returns to his COVID-19 response. There was a 2017 attempt by House Democrats to launch an impeachment process after Trump’s remarks about the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville and calls for another one invoking the emoluments clause of the Constitution in 2018. Then there was the first impeachment, regarding Trump’s demand that Volodymyr Zelensky investigate Hunter Biden’s business dealings in Ukraine before the United States released military aid to the country, and the second impeachment, launched after the assault on the Capitol on January 6, 2021, when Trump had only days left in office.

Would you (or someone you know) like to read my articles in German or French? Please subscribe to my sister Substacks!

As it turned out, none of these attempts to oppose Trump was particularly effective. This was most predictable when it came to the practices and demands that flagrantly broke with the traditions they claimed to defend. To suggest that you can save democracy by exhorting members of the Electoral College to overturn the outcome of the election is absurd. To save the country from “fake news” by going on the air to falsely claim, night after night, that you have the receipts to show that the president is effectively a foreign agent is not much better.

But even some of the tactics that seemed reasonable at the time proved to be ineffective. For example, it turns out that old political cleavages no longer matter when a polarizing figure like Trump turns much of the country’s public life into a referendum on himself. To political elites, the old divisions between Democrats and Republicans were still immensely meaningful in 2016, and so the willingness of both historically Democratic-leaning and historically Republican-leaning professionals to denounce Trump seemed like an objective indication of the danger he posed. But a lot of voters had by then realized that Trump’s arrival on the political scene had forced traditional Democrats and Republicans onto the same side. Fairly or not, these voters accordingly dismissed “bipartisan” condemnations of Trump.

Many of the investigations into and impeachment proceedings against Trump were built on a similar delusion. They assumed that some information they surfaced, or some level of attention they commanded, would lead to a sudden breaking point. A public that seemed largely inured to being scandalized by his behavior would finally come to understand just how abnormal he is; wavering Republicans who secretly hated the man who had usurped their party would suddenly find the courage of their convictions and join with their Democratic colleagues in removing him from office. But those breaking points never arrived. Many Americans remained indifferent to Trump’s alleged misdoings. Virtually all of the Republican senators who privately expressed their hatred of him publicly expressed their support when the decisive votes were tabled.

Each of these tactics turned out to have shortcomings of its own. But more fundamentally, all of them foundered because they were rooted in a mistaken analysis of the situation. For as Trump’s resounding reelection has shown, his success wasn’t an aberration.

This time around, Trump won the popular vote. He was able to vanquish Kamala Harris even though she had far less political baggage than Hillary Clinton and was not subject to a damaging FBI investigation. There is no reason to believe that interference from foreign adversaries made a material difference in the election. Most strikingly, the narrative according to which Trump’s political appeal is restricted to one declining demographic segment of the electorate—widely assumed for the past years to be true even among the country’s leading political scientists—has turned out to be badly wrong. Unlike in 2016, his electoral coalition in 2024 drew heavily on Latinos, Asian Americans, Native Americans, and even African Americans.

All of this means that the task facing Trump’s opponents is much more difficult than it seemed in 2016. The conviction that the diversification of the American electorate will eventually deliver inevitable victories to Trump’s opponents now looks hopelessly naive. The most obvious ideas about how to oppose him have been tested—and found to be wanting. Rather than “merely” getting through a one-time four-year emergency for the republic, his opponents need to figure out how to defeat a political movement that has appeal within every major demographic group—and now threatens to grow into the dominant force of an entire political era.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Yascha Mounk to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.