Help Me Understand… What Will Happen in 2025

Plus, a mid-decadal assessment of my predictions for the 2020s.

Thank you for reading my articles over the past months—I am excited to keep writing my heart out for you in 2025!

In the meanwhile, I thought I would end this year by doing two things. First, I will rate the predictions I made about the future at the beginning of the decade. And second, I am reviving an occasional feature I have particularly come to love. I’m turning to all of you for help in figuring out something to which I genuinely don’t know the answer—in this case, what’s likely to happen over the course of the next twelve months.

What will Trump’s second presidency bring? Will the conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East finally come to an end? Are there going to be any major technological breakthroughs? What major surprises do you expect in the fields of politics and culture, of economics and the arts? Make your predictions here—and I will feature the most prescient ones at the end of 2025!

Over the last days, my inbox has been full of posts from fellow Substackers rating the predictions they made at the beginning of the year. As I was reading these posts, I suddenly remembered that I engaged in a similar—and, truth be told, even more foolhardy—exercise five years ago. At the time, I made a number of predictions for how the decade would go. Since we are now about to cross the midpoint of the 2020s, I thought I would go back over those predictions to see which are on track to prove right—and which are likely to prove wrong.

1. Fading Importance of Social Media

People spend an enormous amount of time and attention on social media today. But the real reason some platforms now influence everything including the contours of public discourse and the American presidential election is not that your cousin is addicted to Instagram; it is that key decision makers mistake the opinions of a small number of politically engaged—and ideologically extreme—people on social media for the views of the general public.

In decades past, newspaper editors knew that cranks and extremists were more likely to submit letters than average readers; they therefore took their opinions with a large grain of salt. Today, decision makers are obsessed with the modern-day descendants of those cranks. The recognition that Twitter and similar platforms do not represent the real world, however, might lessen the political influence of social media.

Social media remains extremely influential today, and it is in retrospect striking that I mentioned Twitter and Instagram but not TikTok. To say that the overall importance of social media has faded is clearly wrong.

And yet, a part of this prediction does ring true. In the middle of the 2020 primary cycle, the predominance of woke slogans on Twitter wrongly gave many influential people the impression that this is what most Americans believed. At times, it even felt as though the loudest voices on Twitter could single-handedly dictate the electoral strategy of the Democratic Party.

In the wake of the 2020 election, Twitter’s hold on public discourse began to fade. Then Elon Musk bought the platform, radically changing whose voices predominated on X, and further eroding its influence. Today, social media retains a key role in society—but the recognition that the posts that get the most likes on Twitter, Instagram or (yes) TikTok don’t necessarily represent the views of most Americans has thankfully spread far and wide.

Rating: 5/10

2. Young People Become Less Political

During the 2010s, young people were very politically engaged. Many of them were aghast at the rise of far-right populism and deeply concerned about inaction in the face of climate change. Thanks to social media, they could easily give voice to that anger. So the assumption that young people will continue to be highly political is tempting.

But in the past, many periods of political engagement were followed by calmer intervals. The student activists of the 1960s and ’70s, for example, were succeeded by the yuppies of the ’80s and the apolitical ironists of the ’90s. So it is just as likely that the current tide of engagement will start to ebb, with many young people slowly disengaging from politics.

Political engagement ebbs and flows. A few months after I wrote these lines, in the summer of George Floyd, youth activism—in part fueled by the strange circumstance that, amidst the COVID-pandemic, it was the only legal way to congregate with friends—reached a record high. But it seems to have been on a downward trajectory ever since. Notably, youth turnout fell by about 20 percent between 2020 and 2024.

More broadly, back in 2020, the widespread assumption was that most young people would skew progressive. The 2024 elections made a big dent in that theory. Americans under 30 were nearly as likely to vote for Donald Trump as for Kamala Harris, and the president-elect now has a positive approval rating among members of this demographic. Compared to the beginning of the decade, it sure feels as though the generation of what were once called “social justice warriors” is giving way to a new generation much less prone to political activism in general and progressive views in particular.

Rating: 8/10

3. Post-Woke

The 2010s ushered in what some commentators are calling the “Great Awokening.” Especially in the United States, white leftists embraced more radical views on identity than they had in the past. But … throughout the past several months, a broad array of left-wing figures—including Dave Chappelle and Barack Obama—have criticized some aspects of the Great Awokening. Perhaps this was inevitable: As these positions gain in power, more people start to pay attention to them, and their illiberal nature becomes harder to ignore. Once exposed, these views may start to fade from the public discourse.

This prediction was pretty prescient. Woke ideas reached their apotheosis in 2020, when Ibram X. Kendi and Robin DiAngelo dominated the bestseller lists, and even mild disagreement with their particular brand of “anti-racism” could get you fired. But they have been on a downward trajectory ever since. Once she became the Democratic nominee for President earlier this year, Kamala Harris studiously avoided reprising the woke talking points that had been so central to her failed primary bid in 2020. In post-mortems about why Democrats lost the election, the party’s lingering association with these deeply unpopular ideas rightly played a major role.

All of this makes it tempting to give myself full marks on this count. But as I have argued in recent weeks, it would be a mistake for opponents of wokeness to declare victory prematurely. For structural reasons, Democrats will find it much harder to dissociate themselves from these ideas than is widely assumed. And just as public opinion swung to the right while Joe Biden was president, it may swing back to the left once Donald Trump takes office.

Rating: 8/10

4. Conservatives Become More Diverse

In most countries, including Germany and the United States, immigrants and religious minorities are more likely to vote for left-wing parties … Most political observers assume that this trend will continue in the coming decades; in America, many political scientists even predict that the Democrats will eventually have an all-but-certain electoral majority because of the growth in the nonwhite share of the population. But if conservative parties have any sense of self-interest, they will finally start to build a broader tent. And if they manage to appeal to immigrant voters with conservative values … Western politics may become less racially polarized.

In the 2024 election, Donald Trump made major inroads among Hispanic, Asian-American and even African-American voters. Highly diverse Florida has gone from a purple to a solidly red state. And while most key members of Trump’s incoming administration will be white males, the list also includes prominent figures such as Marco Rubio as Secretary of State, Tulsi Gabbard as the Director of National Intelligence, Kash Patel as the Head of the FBI, Steven Cheung as White House Communications Director, and Vivek Ramaswamy as co-lead of the Department of Government Efficiency.

The story is even more striking across the pond. In the United Kingdom, Rishi Sunak, a Conservative, became the country’s first Hindu Prime Minister. James Cleverly, whose mother comes from Sierra Leone, was long favored to succeed him as leader of the Conservative Party. Instead, he was bested by Kemi Badenoch, a British-Nigerian who mostly grew up in Africa, and was catapulted to the helm of the party because of her popularity among its elderly membership.

The widespread assumption that “demography is destiny” was clearly wrong—and I must say that I am a little proud to have been among the small band of writers who has been loudly making this point for the past half decade.

Rating: 9/10

5. Cost of Housing Stagnates

One of the most remarkable trends of the past few decades has been the rapid increase in housing costs in the world’s major metropolitan areas… The recent pace of appreciation can’t be sustained for long. Though prices are unlikely to come down, their growth may slow considerably.

The pandemic made housing prices shoot up. Then the unexpected bout of high inflation led many mortgage payments to balloon—while also leading to a rare decline in (inflation-adjusted) housing prices. All in all, this has over the past years led to a comparatively modest increase. Whereas the cost of the average home in the United States grew rapidly over the course of the 2010s, as prices recovered from the 2008 burst of the housing bubble, they have only increased modestly in the first half of the 2020s. (From 2020 to 2023, they have done so by about 3 percent.)

More broadly, there are finally encouraging signs that the longstanding resistance of homeowners to new developments in their neighborhoods may be starting to become less effective. It feels as though a coalition of “YIMBYs” and activists embracing an “abundance agenda” have won the intellectual argument, and some restrictive regulations are starting to be revised as a result. But whether this translates into much more construction—and stagnating prices—by decade’s end very much remains an open question.

Rating: 6/10

6. Rising Wages for the Low-Skilled

For years, incomes in many developed democracies have risen for those at the top but not for those at the bottom. This differential has made many citizens deeply pessimistic about their country’s economic future.

But in the United States, this trend is now reversing. Wages started to rise across the board as the economy reached full employment in the last few years. In fact, in 2019, wages for low-wage earners rose about twice as fast as those for high-wage earners. If other developed democracies start to enjoy a similarly high level of employment—and sympathetic governments encourage a wage hike for those who most need it—the wages of the low-skilled may continue to rise more quickly than they have in the recent past.

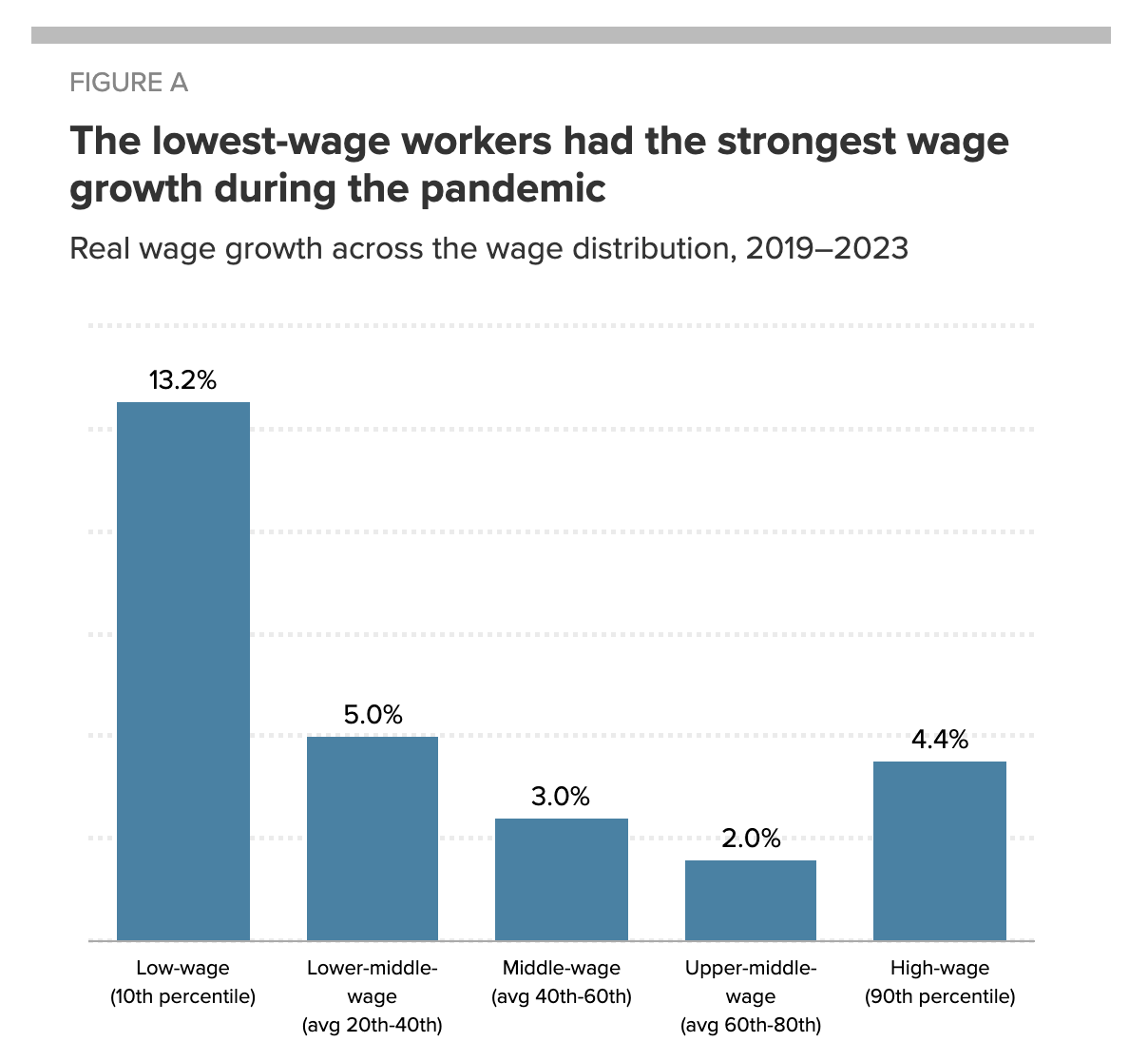

I’m going to count this one as a win. While the wages of those towards the higher end of the wage distribution grew by less than 5 percent between 2019 and 2023, the wages of people at the bottom of the distribution increased by over 13 percent. As a recent report from the Economic Policy Institute summarizes, “in stark contrast to prior decades, low-wage workers experienced dramatically fast real wage growth” in recent years.

Rating: 10/10

7. Global Inequality Falls

The wealth distribution in affluent democracies such as Denmark and Canada has become far more unequal over the past few decades. But across the world as a whole, income inequality has actually been shrinking: Because the incomes of poor people in India or China have grown much more rapidly than those of affluent people in Sweden or Australia, the world is more equal now than it was 10 years ago. So long as parts of Asia and Africa can continue on their recent growth trajectories, this trend is likely to continue in the coming decade.

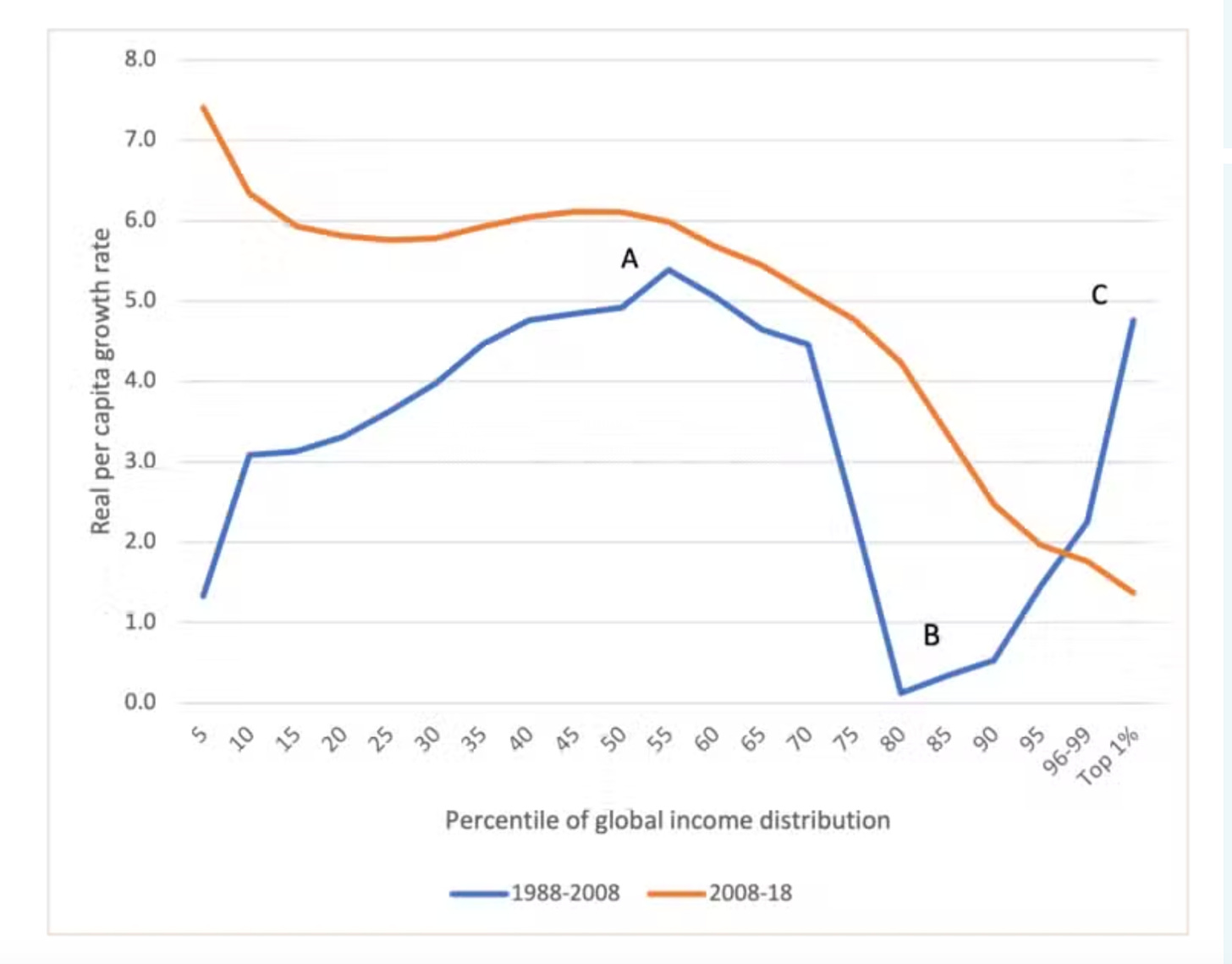

During the 2010s, the discussion about economic inequality was shaped by three fundamental contributions. First, Thomas Piketty’s work seemed to suggest that the return to capital would always outpace the returns to labor, meaning that—in the absence of a big war or a major government intervention—the world would become more and more unequal. Second, David Autor argued that middle-class jobs were becoming much more sparse in America, with most of the wage gains captured by the top. And finally, Branko Milanovic published the “elephant curve” (represented by the blue line in the graph below), suggesting that the growth in per capita income was much more limited for the poorest people in the world than it was for the richest.

Over the course of the last years, all three pieces of this conventional wisdom have slowly given way. Piketty’s work has come under growing and sometimes withering scrutiny. According to one powerful line of criticism, for example, the high returns to capital he identified largely stem from the rapid increase in the prices of houses and apartments in affluent metropolitan areas like Paris or New York—a phenomenon that favors the upper middle-class rather than the oligarchs on whom Piketty tends to focus, and seems like a temporary result of bad housing policy rather than an inexorable outcome of capitalism. Autor has significantly revised his story as the structure of wage growth in America changed; he was one of the first to emphasize that, over the last years, those at the bottom of the income distribution have experienced particularly fast wage growth. Perhaps most importantly, in 2022, Milanovic published an update to his elephant curve. Once he ran the same calculation with new data, the story became much more upbeat: it now shows the fastest wage growth for the global poor, and the slowest wage growth for the global rich (see the orange line on the graph below).

Rating: 9/101

8. Predictions about Populism and Democracy

Finally, I made three related predictions about the future of populism and liberal democracy.

First, I argued that countries that have for a long time been ruled by populist leaders would experience serious crises: “The longer these leaders stay in office, the more the effects of their misrule will be felt by ordinary citizens in their everyday lives.” This, I predicted, would make them vulnerable to popular challenge.

Second, I predicted “the rise of moderate populists.” Figures like Boris Johnson, I suggested, could become “a blueprint for a form of moderate populism—one that still assails (some) democratic institutions, but rejects the more extremist views on race and culture that are commonly associated with far-right candidates.”

Third, I predicted that “liberal democracy may regain its allure.” It may not be too naive to hope, I wrote, that “the two basic values of liberal democracy—individual freedom and collective self-determination—will look stronger in 10 years than they do now.”

I could still make a case for some of these predictions. Jair Bolsonaro lost his bid for reelection, the populist government in Poland has been banished to the opposition, and Viktor Orbàn is much less popular in his own country than he has been for most of the past decade. From Italy to France, there are signs that once-radical populist movements are moderating in meaningful ways. And of late, some serious research in political science has suggested that standard metrics like Polity or Freedom House have vastly overstated recent declines of democratic institutions. Perhaps liberal democracy is in less danger than most political scientists have come to believe?

And yet, this set of predictions feels to me much less solid than most of the others. Many populist leaders who were in office in 2020, from Hungary’s Orbàn to Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan to India’s Narendra Modi and Venezuela’s Nicolas Maduro, remain in power. Boris Johnson grew deeply unpopular and was hounded out of office by his own political party. And with Trump recently re-elected to the White House, it seems at best premature to predict that the era of turbulence for democratic institutions is coming to an end.

Rating: 4/10

Do you think you can do better in predicting the events of the next twelve months—or the next five years? Let me know your predictions, and I will feature the best ones at the end of 2025!

One concerning wrinkle here is that Africa has so far had a very mixed decade; while the per capita growth rate for the world’s poorest has been very encouraging, a continuation of this trend will require large, fast-growing countries like Kenya and Nigeria to improve their economic performance.

"Reports of my death have been greatly exaggerated" - Wokeness

The notification I received immediately prior to reading this article concerned ongoing efforts to write transgender ideology into State mandated 5th grade educational standards.

Woke hasn't died, hasn't even significantly retreated on every front, it simply shifted more from the highly visible "shouting in the streets" phase of activism to the "quietly implementing policy through governing institutions" phase. I get it, that's a lot less interesting for news coverage than pictures of purple-haired protesters screaming and waving signs, but then again the protesters already got much of what they said they wanted. Those gains haven't been consistently rolled back, they've more been consolidated and formalized into a "new normal" where DEI, Critical Race Theory, Transgender Ideology, etc are written directly into institutional standards. You could probably get away with saying that woke "peaked" in 2020, but a more accurate statement would be that it hit a plateau. We've yet to see culture or policy return anywhere remotely close to the baseline prior to the Great Awokening. Really, it's not like there was much room left to get MORE extreme than it already was. 'It stopped getting worse' should not be confused for 'It stopped'.

One hardly knows where to begin.

We seem somehow to have elected a new administration composed largely of unqualified ne’er-do-wells, sycophants, authoritarian apologists, misogynists, liars, election deniers, violence inciters, drunks, and assorted nuts; all headed by two billionaire dilettantes whose primary view of the US government is as a shiny toy with which to play without regard to the fact that it is also the most crucial, the riskiest, and the most complex experiment in human government ever attempted. Neither do they seem to understand that their playground includes several hundred million angry, frustrated, confused, saddened, worried, desperate, and deeply diverse and divided citizens, many of whom don’t seem to understand the reasons for or the nature of that experiment in which they are both inheritors and participants, whether they like it or not.

What could possibly go wrong.

I hesitate to make predictions. Or rather I feel a total lack of sufficient wisdom to do so. What I do have, as an amateur anthropologist who once majored in human origins and evolution is a sense of where we’ve come from and what we brought with us across the boundary from mammals to primate to human. That tells me that our essential nature is one of innate parochialism, genetically honed by millions of years of survival in small groups in which every member knew each other intimately and exactly what his or her role was in that game.

In many ways we are still that creature, self-thrust over the past several millenia into a world so different from the one into which we were born as to be beyond imagining. And we haven’t yet learned what to do about that. But evolution also endowed us with a brain with a far greater capacity than we needed. With it we have over time created a complex world of economic, political, social, religious, and technical complexity in which that parochialism is far more a curse than the necessary survival mechanism it once was.

This nation was created in the hope that with the proper governmental structure, we could mitigate the more destructive aspects of that parochialism by finding a way to co-exist with each other as a single polity, under our own combined control, no matter how diverse our experiences and opinions.

But demagogues like Trump and Musk are and always have been skilled in exploiting that parochialism for their own ends. The results have almost always been problematic if not downright disastrous. And after August 6th, 1945, that potential for disaster has grown exponentially.

It remains to be seen if we can remain, in the words of one who understood as well as any American who ever lived both the promise and the peril of our Novus Ordo Seclorum, ’the last best hope of earth’.

At the age of 80, I have to admit to a lack of optimism. I recall John Kennedy’s words following the closest we’ve yet come to succumbing to that parochialism, “...we all inhabit this small planet. We all breathe the same air. We all cherish our children’s futures. And we are all mortal.”

But I don’t know if we can come to understand that in time.