You’re (Probably) Thinking About Extroversion All Wrong

No, it’s not about whether you get energy from being around people.

Have you been enjoying my writing? Please support my mission and help sustain this Substack by becoming a paying subscriber. An annual subscription will cost you less than a weekly cup of coffee at Starbucks—and make my day.

You’ve probably heard some version of this conversation:

A: Your friend Tina was the life of the party—cracking jokes, dragging everyone to the dance floor, just a huge extrovert.

B: Tina is the best! But, you know, being lively doesn’t really have anything to do with being an extrovert…

A: What are you talking about? She’s like the definition of outgoing!

B: Yeah, but that’s not how psychologists think about extroversion. It’s really more about how hanging out with people affects you. Extroverts get energy from being around others. Introverts drain—it’s like their social battery gets depleted. Tina could totally be an introvert if she is, like, craving some alone time today.

Full disclosure: About a decade ago, a friend, sounding very much like B, explained to me how psychologists akthually think about introversion and extroversion. And since then, I too have sometimes been the know-it-all in this conversation, explaining how the “real” definition of extroversion is all about gaining or expending energy in social situations.

The idea that being extroverted is all about being outgoing probably remains, just about, the conventional wisdom. But the idea that really it’s all about whether socializing charges or drains your social battery has quickly become nearly equally widespread; it is now what we might call the “counter-conventional wisdom.”1

But, as is often the case, the counter-conventional wisdom turns out not to be any more accurate than the conventional wisdom. Indeed, there are at least two problems with the notion that the right way to think about extroversion and introversion is in terms of whether you gain or lose energy from socializing.

Are you in or near London? Join me for a free community meet-up at The Perseverance, on Lamb’s Conduit Street, on Wednesday, June 4th, from 6pm! I’m excited to meet many of you there! — Yascha

The first problem is that the counter-conventional wisdom is wrong about both the original meaning of the term and about the way most psychologists use it today. Based on how many generally smart and well-informed people in my social circle tend to use terms like introversion and extroversion these days, I wrongly came to believe that most psychologists conceive of this character trait roughly in the manner implied by the metaphor of the social battery; but when I delved into both older writings and recent research about extroversion for this article, I learned, to my surprise, that this simply isn’t the case.

The second problem is that the older and more conventional meaning of the word is actually useful. It’s important to be able to express that somebody is very outgoing, has a big personality, and tends to be the life of the party. And while there are all kinds of ways to describe those qualities—indeed, I just used three in the last sentence—it is helpful to be able to sum up the character trait that stands at their root in a single word. To call somebody like Tina an extrovert is the way that we’ve done that for the better part of a century.

The counter-conventional wisdom about extroversion obscures more than it reveals. It’s time for a wholesale conceptual reexamination of what we talk about when we talk about introverts and extroverts.

Extroverts… Just Wanna Have Fun

The terms introvert and extrovert were coined by Carl Jung. From the start, they were about the extent to which people seek stimulation from the outside world. An introvert, in Jung’s formulation, is somebody with an “attribute-type characterized by orientation in life through subjective [i.e. internal] psychic contents.” By contrast, an extrovert is somebody with an “attribute-type characterized by concentration of interest on the external object.” Jung also recognized that some people may have a mixture of these traits, laying the groundwork for the later characterization of big parts of the population as “ambiverts.”

Jung’s language can be a little arcane. But in the main, his description of introverts and extroverts is strikingly similar to the conventional, not the counter-conventional, way of talking about these concepts today. An introvert, he claimed in an early lecture,

Holds aloof from external happenings, does not join in, has a distinct dislike of society as soon as he finds himself among too many people. In a large gathering he feels lonely and lost. The more crowded it is, the greater becomes his resistance … His relations with other people become warm only when safety is guaranteed, and when he can lay aside his defensive distrust. All too often he cannot, and consequently the number of friends and acquaintances is very restricted.

(Doesn’t quite sound like Tina, does it?)

Over the course of the following century, psychologists have, thanks to the contributions of researchers from Hans Eysenck to Lewis Goldberg, significantly refined the theory of personality. But while Jung’s blunt language would make today’s academic psychologists blush—as they rightly insist, there is nothing wrong with introverts—they for the most part have preserved his original conceptualization.

Take, as an example, the way in which The Big Five Personality Test defines extroversion. Also known as OCEAN for the five traits it assesses (openness to experience, conscientiousness, extroversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism), this test has proven its usefulness by predicting a range of important life outcomes significantly better than its alternatives. It has, for a number of decades, been the most widely used and broadly trusted personality test in academic psychology.

According to one canonical version of the OCEAN test, extroversion should be defined as “the personality trait of seeking fulfillment from sources outside the self or in community; high scorers tend to be very social while low scorers prefer to work on their projects alone.” The focus on whether somebody is outgoing, rather than on how they “charge” or “deplete” their social battery, is also clear from the questions in the test which measure a respondent’s degree of extroversion. Test respondents score high on extroversion when they say that they “start conversations,” “feel comfortable around people,” and “are the life of the party.” They score low on extroversion when they say that they “don’t talk a lot,” “keep in the background,” and “keep quiet around strangers.”

So where does the popular misconception that extroversion is “really” about whether somebody gains or drains energy from social interaction come from? The most likely culprit is the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), a personality test that is taken less seriously by academic psychologists, but has found greater popularity in the business world.2 When describing what it means to be an extrovert, many popular sites offering free MBTI tests invoke the metaphor of the social battery. According to the website Truity, for example, “introverts are energized by spending quiet time alone or with a small group” whereas “extroverts are energized by spending time with people and in busy, active surroundings.” But even on the actual MBTI test, most questions regarding extroversion have nothing to do with your social battery.

On the test used by Truity, for example, a single question used to assess the trait of extroversion gets at the metaphor of the social battery; test takers are asked whether or not “being around lots of people energizes me.” The vast majority of questions assessing extroversion, however, have nothing to do with energy. Test takers are asked whether they “avoid being alone,” “enjoy chatting with new acquaintances,” or “would enjoy attending a large party in [their] honor.” The questions go on and on in the same vein, asking respondents whether they get “a thrill out of meeting new people,” “love to make new friends,” or whether (inversely) they “avoid noisy crowds” and “find it challenging to make new friends.” While a single question asks about whether respondents gain energy from social interactions, over 20 ask whether or not they are outgoing.

The idea of the social battery is a highly viral intellectual meme. But it has little grounding in either the history or the contemporary practice of psychology. For the most part, even tests which claim to measure extroversion in these terms actually don’t. Does that mean that we should altogether dismiss the idea?

Of Chargers and Drainers

In a sense, the whole debate about the “real” definition of introversion and extroversion is a red herring. The most important question is not which definition is historically authentic, or even which dominates among academic psychologists today; it’s which definition best helps us understand people—and ourselves.

From that vantage point, I can see merits both in the conventional and in the counter-conventional wisdom. It is helpful for humans to be able to express whether somebody is lively and outgoing or shy and socially recalcitrant. It is also helpful for humans to be able to express whether somebody gains energy from social interactions or finds them to be draining. Instead of choosing between these two separate sets of concepts, we should develop a vocabulary which allows us to name both of them—ideally by two intuitive and distinct sets of names.

My suggestion is to stick with extrovert and introvert to denote the original meaning of these terms: that some people are very sociable and others prefer to keep to themselves. We could then use a new set of terms to express the metaphor of the social battery. Tina, for example, is probably a charger, someone who gains a ton of energy from hanging out with people. But she might also turn out to be a drainer, someone who—however outgoing she may seem—is totally depleted after a big party.3

But there is one more problem we need to solve before embracing the metaphor of the social battery. At present, it assumes that the tendency to gain or lose energy is unidimensional. According to most sources that describe the concept, those whom I’m calling chargers have a general tendency to gain energy from social interactions; they are energized by socializing with just about anybody. Similarly, those whom I’m calling drainers have a general tendency to expend energy in social interactions; they get drained by socializing with just about anybody. Surely, that is overly simple.

I myself am extremely extroverted; according to the OCEAN test, I am more outgoing than 96% of the human population. I am also pretty sure that I am a charger; generally speaking, I find it energizing to be around people. But though most social interactions do indeed give me energy, this certainly isn’t universally true. Some people and some situations, even to me, are… fucking draining.

The inverse is likely true for all but the most extreme introverts. They may find many people and many social interactions to be draining. But even they may get some energy from hanging out with a beloved sibling, from seeing their partner after weeks apart, or even from chatting with a relative stranger who is particularly adept at making them feel at ease.

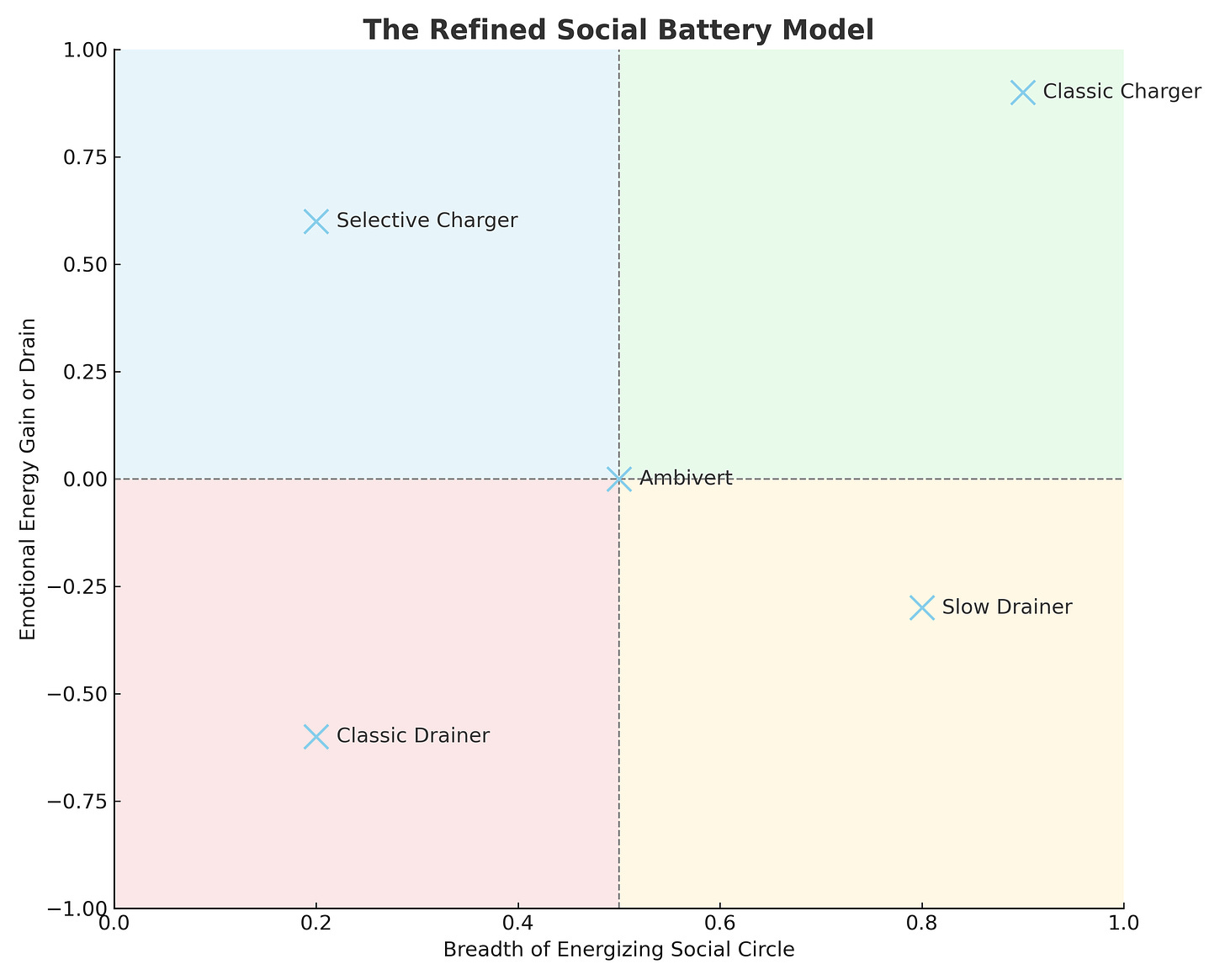

This is why it seems to me that the metaphor of the social battery is in need of significant refinement. Chargers and drainers are not (just) defined by whether they charge by being around people—they’re (also) defined by how wide the circle of those who charge their social battery is.

Chargers are energized by a wide range of people and social situations. Drainers find a wide variety of people and social interactions to be exhausting. The extent to which you are a charger or a drainer depends on two dimensions: not only on how strongly you gain or lose energy from interacting with somebody in a specific situation but also on the range of social situations in which you do so.

Avoid the Vampires

The refined metaphor of the social battery prompts an obvious follow-up question: Why do I get energy from most people—but find a few people to be really draining? And why do introverts generally find it exhausting to be around people—but might, on rare occasions, find it surprisingly easy to chat with a stranger?

Some of this is idiosyncratic, rooted in the happenstance of whether two individuals “are on the same wavelength” or “rub each other the wrong way.” But part of it is likely about which individuals tend to give others energy and which individuals tend to drain the energy of others. In other words, there aren’t just “chargers,” who generally gain energy from social interactions; there are also “energy radiators” who tend to energize the people with whom they come into contact. Similarly, there aren’t only “drainers,” who lose energy from social interaction; there are also “energy vampires”—people who have such a negative vibe, or are so self-absorbed, that they leave even classic extroverts, like myself, deeply exhausted.

Want to hear me in conversation with leading thinkers of our time? To catch up on recent episodes of The Good Fight with the likes of Francis Fukuyama and Larry Summers—and avoid missing out on even more exciting ones we have in the works—sign up for ad-free access to full episodes by becoming a paying subscriber today!

A lot of the promise of personality research lies in the idea that a recognition of yourself will provide you with a way to hack or optimize your life. And there is definitely something to that promise. For many introverts, in particular, a better understanding of their own personal predilections—coupled with growing social recognition of their particular needs—has proven liberating. Rather than being seen as aloof or socially inept, they are now recognized as a natural and common personality type, one that is neither better nor worse than their extrovert brethren.

But as in many other areas of our culture, I also worry that the promise of liberation through “mesearch” about our own personality is sometimes overstated. It is certainly useful for each of us to better understand whether we are extroverted or introverted—or, for that matter, whether we are chargers or drainers. But the far more important life hack consists in learning to categorize the other people in our life—and avoid those who are detrimental to our well-being.

Introverts and extroverts, chargers and drainers alike can enjoy having a rich social life as long as they follow a simple piece of advice: Whatever you do, avoid the energy vampires who sap the joy and energy of anybody with whom they come into contact.

I’m working on an essay about the concept of conventional and counter-conventional wisdoms more broadly. Stay tuned.

Compared to the Big Five Personality Test, the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) has several key weaknesses. One difference stems from how each framework conceptualizes personality traits. The Big Five treats traits like extroversion as continuous dimensions: an individual might fall at the 20th, 49th, 51st, or 80th percentile, with the test capturing fine-grained variation across a spectrum. The MBTI, by contrast, uses binary typologies, sorting individuals into one of two discrete categories (e.g., introvert or extrovert) for each of its four axes. As a result, someone scoring just below the midpoint on extroversion (the equivalent of the 49th percentile on the Big Five Personality Test) might be labeled an Introvert while someone just above (the equivalent of the 51st percentile) would be considered an extrovert—despite being nearly identical in behavior.

Another criticism of the MBTI lies in what academic psychologists call the “construct validity” of some of the traits it purports to measure. MBTI dimensions such as "Sensing vs. Intuition" and "Judging vs. Perceiving" are not very clearly defined and have shown little predictive power in empirical studies. By contrast, the Big Five includes dimensions like conscientiousness and neuroticism, which have been extensively studied and found to correlate with important life outcomes, from job performance to mental health.

Of course, introducing new terms is hard, and most people aren’t likely to get on board anytime soon. So in the meantime, we can—at the risk of confusion—use the original terms while bearing in mind that, depending on the context, they could actually be referring to two rather different sets of concepts. In fact, that is precisely what people are doing when they suggest, for example, that Tina may actually be an “extroverted introvert.”

I have a patient to see in a few minutes so have to be brief. I am familiar with the various definitions of introverts and extroverts. My problem with all the labels we use for personality traits or psychological traits is that they are very poor descriptors of an individual's complexity. They are gross simplifications and either imprecise, or precise but only in certain circumstances. As an example of the latter, a person's level of extroversion may be influenced by their stress level, their physical state (say being premenstrual, or fighting off a cold), or whom they are associating with. As a clinician I find all these labels misleading or worse because people tend to adopt them as an identity. In certain contexts a label can be helpful. The social battery (second definition) is useful for me when I have someone who is depressed and needs to engage in activities that are going to energize them and not deplete them. If the depressed person likes being around others, but finds it draining, then advising them to go to parties is going to make them more depleted and more depressed. I need to find activities that are enjoyable and not draining for that person. On the other hand if I am not in a clinical role and am planning a party for a friend, then if the friend enjoys lots of people (first definition of extraversion) then I am going to plan a party with a lot of people and perhaps in a public setting.

Got to run. Interested to hear what others have to day.

Interestingly, Jung's original conception of extroversion is less people-oriented than any of the usual conceptions. An "attribute-type characterized by concentration of interest on the external object" could describe someone who gets stimulation from viewing art or visiting new places, with or without significant social interactions. It still describes something different from the inward-focused idea of introversion.